Proximity and market size have traditionally made the United States an attractive destination for Caribbean exports. Belize is no exception to this rule, as documented trade with the USA dates back to the late 1800’s (Chicle, Mahogany and Bananas). With Caribbean and Latin American governments becoming independent and more democratic in the early 1980’s, the USA initiated the first phase of the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI), the Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act (CBERA). The CBI programme started 1st January, 1984. As stated by President Ronald Regan in his Presidential Proclamation 5133[1], “ CBERA confers authority upon the President to proclaim duty-free treatment for all eligible articles from any country which has been designated a “beneficiary country” in accordance with the provisions of section 212 of the CBERA.” Adding to the robustness of the CBI, is the Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA) signed in 2000. This act extended the number of goods that benefit from duty free status when imported into the USA by 259 non-agricultural goods, such as textiles and petroleum[2]). For Belize to continue accessing these benefits, as it has been doing, a clear understanding of the key rules and sections governing the CBI is needed.

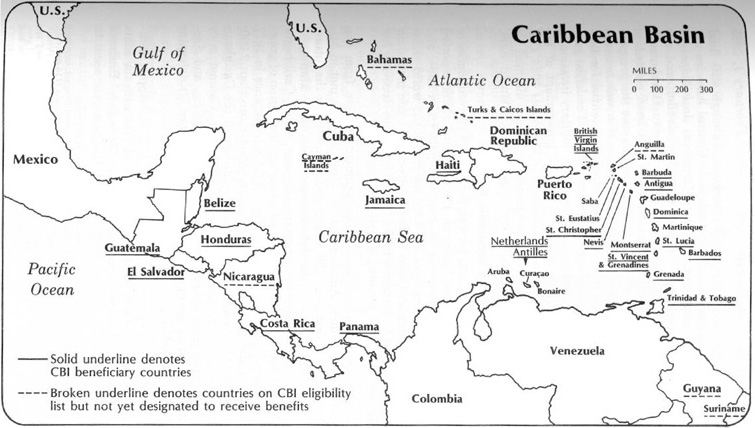

Belize joins 17 other Caribbean countries (CARICOM members[3], Aruba, Curacao and the British Virgin Islands) as beneficiaries under President Reagan’s CBERA. Listed as a preferential trade agreement by the WTO, CBERA offers access to a market of over 320 million, which incentivizes expansion of production in beneficiary countries. CBERA[4], according to the WTO guide, confers duty free access to approximately 5,700 8-digit tariff lines. For Belize, which has access to 5,152 lines at preferential rate of which 5,090 are duty-free, access to the preferential rate is dependent on its exports meeting the origin requirements. (U.S. Code Title 19 Chapter 15 § 2703) Goods eligible for preferential access under CBERA, shall be any article which is the growth, product, or manufacture of Belize if (A) that article is imported directly from a beneficiary country into the customs territory of the United States; and (B) the sum of (i) the cost or value of the materials produced in a beneficiary country or two or more beneficiary countries, plus (ii) the direct costs of processing operations performed in a beneficiary country or countries is not less than 35 per centum of the appraised value of such article at the time it is entered[5]. The first rule implies that goods that are merely transhipped through Belize will not qualify for preferential access. The second rule allows for Belize to access resources for manufacturing from other beneficiary states. Along with these clear and transparent rules, the amount of cost incurred in the value of the product must be significant, at least 35% or greater, to confer origin. Taken together, these rules ensure that trade with the US under CBERA supports the development of local industry. While these rules were adopted from the US Generalized System of Preferences[6] (GSP), CBERA expanded the total list of products eligible for duty free access by allowing products based on origin criteria (unless explicitly banned) and not by Executive order, as in GSP. This distinction resulted in an increase of over 2,200 tariff lines for products that could be traded duty free. Goods that are eligible for duty free treatment under CBERA are designated with an “E” in the US Harmonized Tariff Schedule.

Like most unilateral trade arrangements, beneficiary status under the CBI hinges on several responsibilities and obligations by the recipient countries. Section 212[7] of the CBI outlines the following actions that Belize must maintain/practice to secure its market access: 1) remain a non-Communist country, 2) refrain from the expropriation of property owned by Americans, including business, without prompt, adequate and effective compensation 3) refrain from nullifying any form of intellectual property, 4) recognize as binding arbitral awards in favor of American businesses and persons, 5) refrain from offering preferences to other developed countries that would displace US commerce, 6) refrain from broadcasting copyrighted material through government entities, 7) cooperation to prevent narco-trafficking into the US and 8) remain signatory to an extradition treaty with the US. The subsequent section of the act clearly expresses that the US government will not allow any consideration to countries that eliminate US commercial interests due to trade agreements, refuse to cooperate on drug trafficking prevention and fail to sign an extradition treaty with the US, with the others being grounds for removal after consideration by the President and report to Congress[8]. These parameters highlight the influence of US foreign policy in beneficiary countries, which have traditionally been allowed due to the importance of the American market to regional economies. With the CBI being a unilateral agreement, beneficiary countries must follow the prescribed guidelines or face a removal of benefits.

Belize has traditionally been one of the beneficiary countries that has taken advantage of the preferential access granted under the CBI. This can be attributed to the nature of Belize’s export basket, agriculture and agro-processed products, and the history of American investors in Belize (chicle, shrimp and papaya). The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) submits a biennial report to Congress on the operation of the CBERA, highlighting the access of beneficiary countries and any changes in the administration of the system. In the 2017 Report the Congress, the USTR reported the following:

“Total value of U.S. imports for consumption from beneficiary countries in 2016 was $5.3 billion, a decrease of 24 percent from 2015 and down 58 percent from 2006. U.S. imports under the CBERA program were $870.9 million in 2016, from $1,541.8 in 2015.

The decline in U.S. imports from CBI beneficiaries was mostly due to lower petroleum prices and lower imports because of increased domestic U.S. petroleum production. U.S. imports of textiles from CBERA countries also declined by 5 percent.[9]”

The US International Trade Commission, in its report on the impact of CBERA on local industries and beneficiary countries, revealed that Belize maintained one of the highest CBERA utilization rates, with rates being 82.3, 78, 62.5, 48.9 and 29%[10]. The report further indicates that “Belize has shown a utilization rate over the same period of over 60 percent on average, although falling to 49 percent in 2015 and a sharp decline to 29 percent in 2016; Belize’s principal export under the program, crude petroleum, has suffered with the recent worldwide decline in oil prices.[11]” During this period, petroleum exports to the US under CBERA fell from USD 101.6 million in 2012 to zero in 2015 & 2016[12], directly reflecting a reduction of significance in Belize’s petroleum industry. As it relates to agriculture, Belize was the only exporter of orange juice to the US under CBERA. The country lost US 1.5 million dollars between 2012 and 2016, due to citrus greening and changing weather patterns[13]. As the Belizean export sectors continue facing adjustment, it will remain the priority of the Government of Belize to secure market access based on transparent and predictable rules.

Founded in 1984, CBERA has created an avenue for Belize and other beneficiary countries to facilitate export diversification and economic growth. With its benefits well documented, the Belizean government should remain vigilant of any changes in US foreign trade policy with the Caribbean and Central American region. The current unpredictability of the US trade policy directorate points to a re-evaluation of the trade agreements and systems that the US is party to, with the view of supporting greater reciprocity. This will create an opportunity for CARICOM to gauge the interest of the US Executive in considering a CARICOM-US FTA, which would effectively end the CBERA program. While considerations of an FTA are premature at this point, it would still serve the economy well to continue establishing private sector relationships between Belizean exporters and American importers. Understanding the intricacies of CBERA should incentivize exports by the Belizean private sector.

[1] Presidential Proclamation 5133, “Implementation of the Caribbean Basin Initiative, accessed on Feb 17, 2018, ” https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-98/pdf/STATUTE-98-Pg3527.pdf

[2] World Trade Organization, Preferential Trade Agreements Database – Caribbean Basin Recovery Act, accessed Feb 19, 2018, http://ptadb.wto.org/ptaTradeInfo.aspx

[3] Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago and Suriname.

[4] CBERA Guide, Accessed February 19, 2018, http://ptadb.wto.org/docs/US_CBERA/2016/US%20CBERA%20guide%202016%20FINAL%20En.pdf,

[5] 19 U.S. Code § 2703 – Eligible articles, Cornell Law School – Legal Information Institute, Accessed Feb 19, 2018 https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/19/2703

[6] The GSP is a U.S. trade program designed to promote economic growth in the developing world by providing preferential duty-free entry for up to 4,800 products from 129 designated beneficiary countries and territories.

[7] Public Law 98-67, “Title II – Caribbean Basin Initiative”, pg.385, accessed Feb. 18, 2018 https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-97/pdf/STATUTE-97-Pg369.pdf

[8] ibid

[9] Twelfth Report to Congress on the Operation of the Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act, “Executive Summary”, page iii, United States Trade Representative, Accessed Feb 19, 2018. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/assets/reports/2017%20CBI%20Report.pdf

[10] ‘Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act: Impact on U.S. Industries and Consumers and on Beneficiary Countries 23rd Report 2015–16 – Page 63 ‘, United States Trade Representative, Accessed Feb 19, 2018. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4728.pdf,

[11] Ibid.

[12] ‘Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act: Impact on U.S. Industries and Consumers and on Beneficiary Countries 23rd Report 2015–16 – Page 93 ‘, United States Trade Representative, Accessed Feb 19, 2018. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4728.pdf, Page 93 (follow above citation method)

[13] ‘Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act: Impact on U.S. Industries and Consumers and on Beneficiary Countries 23rd Report 2015–16 – Page 100 ‘, United States Trade Representative, Accessed Feb 19, 2018. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4728.pdf, Page 100